Iran on Twitter, but why not Facebook?

G. R. Boynton

Iran was rather suddenly back in the news. The Parliamentary election on March 2, 2012, negotiations about Iran's drive to become a nuclear power, Israel's concern as Netanyahu and Obama met, Ali Khamenei's comments on the results of the meeting, the agreement to start anew the negotiations with Iran about their nuclear developments and the agreement of Iran to permit IAEA inspectors to enter new locations -- in very short order these events generated quite a lot of attention.

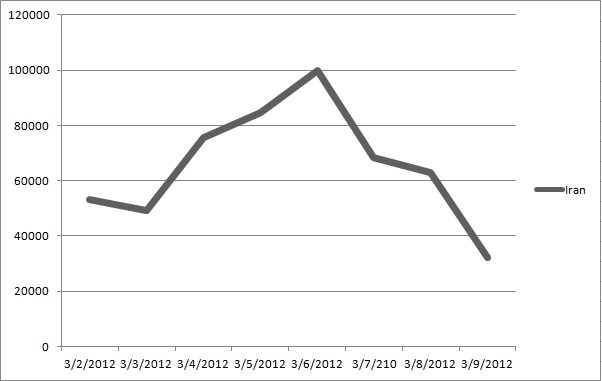

The number of Twitter messages per day mentioning Iran is shown in figure 1.

|

There were 50,000 messages on the second of March. The number of messages peaked on March sixth, which was the day the agreement to resume talks on Iran's nuclear program was announced, with 99,736 messages. And then the number fell off to 32,000+ on the ninth.

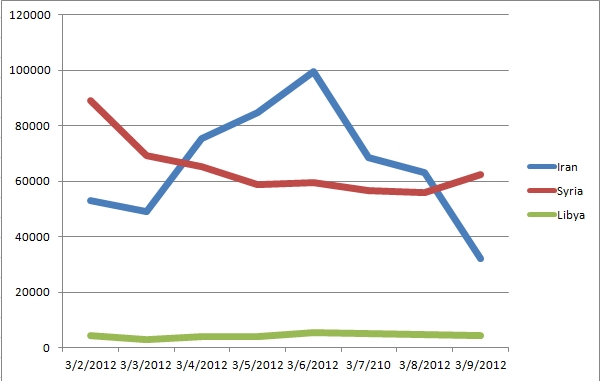

Those are big numbers, but it helps to have comparisons to assess what 'big' means in any case. Figure 2 gives the same numbers for mentions of Iran and adds mentions of Syria and Libya.

|

There were 89,000 Twitter messages on March 2 mentioning Syria. This was, of course, a period when the Assad troops were bombarding neighborhoods in various cities that were locations of opponents of the regime. Many of the messages were screams for help. Then the number per day fell to just over and just under 60,000 per day. The Libyan revolt was long resolved by March 2012, and the number of Twitter messages per day were in the range of four and five thousand.

Okay, but why not Facebook? There are roughly 200 million Twitter accounts and 875 million Facebook accounts [N. B. they go up every month so this is as of spring of 2012]. That is four times as many people on Facebook as on Twitter. Would one find four times as many messages? It is easy to answer that question.

On March 7 and March 9 at approximately 4:45 p.m. I used Archivist, a program that searches the Twitter data base for public tweets, and openbook, which searches the Facebook data base for public messages, to search for messages mentioning Iran. The number of messages for the preceeding thirty minutes are given in the table.

March 7 4:12 to 4:47 |

March 9 4:14 to 4:45 |

|

| Twitter messages | 1474 |

1490 |

| Facebook messages | 62 |

40 |

Twitter will respond to a search with at most 1,500 messages. The search at 4:47 and 4:45 found almost 1,500 messages. The 1,500 messages had been posted in the previous, roughly, 30 minutes. The search for messages on Facebook involved a search and then taking the number of messages that had been posted in the previous 30 minutes.

The differences are striking -- 1,500 to just over and just under 50. There are two things to be said about the differences between communication via Twitter and communication via Facebook. One, by default messages posted to Twitter are public. It is possible to post private messages, but very few people do. By default messages posted to Facebook are private; they are seen only by one's friends. It is possible to post messages that are public, but very few people do. Two, messages posted to Twitter are just that. They are individual messages that are posted. The public messaging on Facebook almost all centers around pages. People may be able to post messages on a page or they may simply like or dislike the page. Pages are organized by as many different groups as one can imagine. Thousands of corporations have Facebook pages. Many governments and government agencies have Facebook pages. And the ones relevant to Iran and Syria have been established by disaffected individuals and groups. They have been seen by many thousands of people and many are sites with photos and videos of the revolts and the response of the governments.

What you can learn from the two new media 'giants' is rather different. Both have been important in political communication just as has YouTube, as well. What they have in common is greatly expanding the public domain -=- though in somewhat different ways. Individuals now are able to reach the world as mainstream media persons have been able to do for half a century. The discussion of foreign policy is becoming open to individuals in a way that disrupts the monopoly of what has been the media. Facebook, Twitter and YouTube are the new media.

But they are different domains of communication. What is distinctive about Twitter is the public messaging by individuals. What is distinctive about Twitter is voice. For scholars the messages posted to Twitter help us understand what people are paying attention to and how they are articulating their reaction to the objects of their attention.

From March 2 through March 9 I collected 526,151 Twitter messages that mentioned Iran, 516,912 messages mentioning Syria, and 35,594 messages about Libya. More than a million messages in eight days are not available for every subject that would involve foreign policy. But if you want to know what people are saying about Iran or Syria or many other world events it is hard to beat Twitter.

How do you do it?

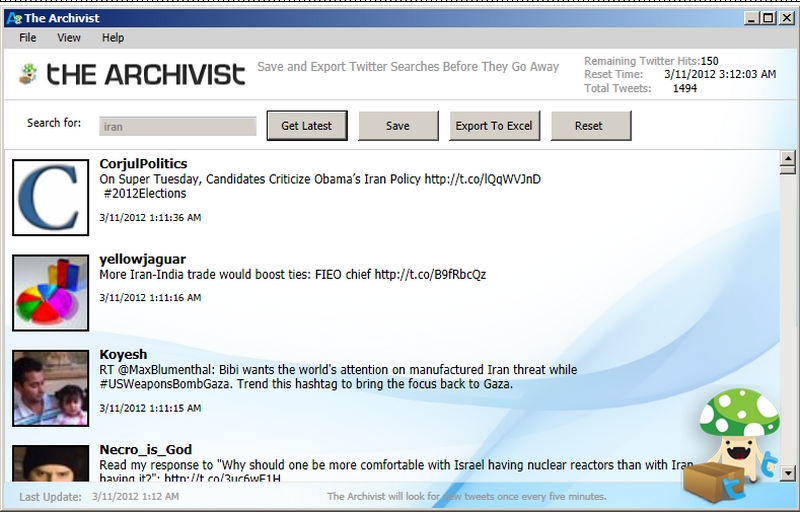

The simple procedure is Archivist. It runs on computers with the Windows operating system. It is free. It is easy to use. You start a search and leave it running. It does the search every five minutes and adds what it finds to a file that it created when you originally saved the file. It counts messages by day and by author. And it exports a tab delimited file that Excel will read, but that any editor that will read a .txt file can read.

You can download the program from http://visitmix.com/work/archivist-desktop/

Once installed you can search and obtain Twitter messages. It looks like this.

|

At the top, right hand corner it gives the time and the current number of Twitter messages found. This view displays Twitter messages with the photo associated with the author of the tweet. There are two other views. One view gives a timeline with the number of messages per day. The third is a pie chart with the names of persons and the number of messages each posted.

The data the program collects are: the unique number assigned to the message by Twitter, the Twitter username, the date, the time, and the status message.

The program cannot, without intervention, collect more than 1,500 messages every five minutes. That means no more than 18,000 an hour. Message streams very rarely contain more than 18,000 messages an hour, but when they do you lose messages. You can, of course, hit the get latest button more often than every five minutes and increase the results of the search.

In this example the search term was iran. However, you can do any of the variety of searches that Twitter permits. A description of the various search operators is at https://support.twitter.com/articles/71577

Twitter has more information than Archivist collects. If you need more than this you will need to write a program that accesses the Twitter API to obtain the additional information.

© G. R. Boynton, March 11, 2012