Now that's going viral: #ScariestWordsEver "President Palin"

G. R. Boynton

At 10:42 the evening of February 3 theUSpresident wrote: #ScariestWordsEver "President Palin".

Twitter users play a word game. Someone initiates a word, such as #ScariestWordsEver, and the game is what you put around the word. The object is to bring a smile to the face of people who read it. And if they smile they will pass it on. In the next couple of hours theUSpresident's tweet was retweeted 945 times. Over the next couple of days this message or some version of it appeared on Twitter 6,500 times.

theUSpresident's message was part of a much larger game. During the same time period there were more than 200,000 messages that contained the word #ScariestWordsEver. Almost anything you can imagine was put around that word-phrase. One of the more obvious "I'm pregnant." But I am going to focus on theUSpresident's message.

How does a single message become 6,500? The standard answer -- it went viral. But that is not an answer; it is a name. The name is an identification rather than an explanation. So, how does going viral work in this context?

'Going viral' is derived from the spread of diseases. A spread that we call an epidemic. We understand the spread as a function of contact and infection. I have the 'bug.' I come in contact with you. There is some probablility that the contact will result in you acquiring the bug. And iterate; it just keeps happening until everyone prone to getting the bug has gotten it through contact. That seems very similar to the spread of jokes, ideas, news, and other messages on Twitter. Twitter is a contact sport. You write. I come into contact with what you wrote. If I am infected with the humor then I pass it on, and other people come into contact. And "#ScariestWordsEver President Palin" became an epidemic. Well, a small epidemic.

There is a standard characterization of the spread we call an epidemic.

At the beginning of the process one person comes into contact with a few people. But each of those who is infected comes into contact with the same number of people in a second round. So the second round there is not just one person in contact with others; there are now many people in contact with others. There are more people in contact at time 2 so the bug spreads to a larger group at time 2 than it did at time 1. At time 3 there are even more people spreading the bug to their contacts. Eventually everyone who is going to have it has had it. And that logic gives a distribution in time. The standard way to look at the distribution is in terms of the total number of people infected in the epidemic. We do, afterall, care about the size of the epidemic. But it is equally possible to look at the distribution of the number of infections in time; how many for each time period. By this logic it is a normal distribution. It looks like Figure 1. The one exception to this would be a case where the initial bug was in contact with every other person in the population at the same point in time. Then it would be a one time period process.

|

|

Figure 1 |

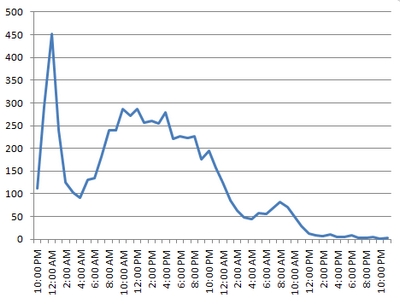

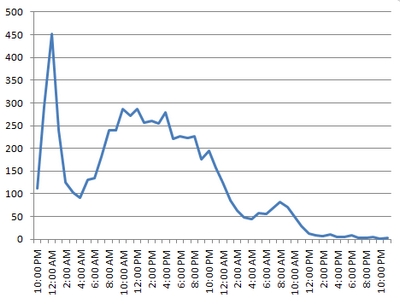

Figure 2 |

So far this all seems plausible enough except the spread of theUSpresident's tweet did not look like Figure 1. The distribution of the incidence of these twitter messages in time looked like Figure 2. And that looks like one-half of a normal distribution with a few dips along the way.

The dips are easy. They both hit 'bottom' at 4 a.m. Twitter people do tend to avoid sleep, but almost everyone has to be asleep, and not tweeting, at 4 a.m. It is the very rapid upsurge that is hard to understand given the logic of epidemics. And that is the puzzle. How was this going viral both similar to a contact and infection process, and it could leap from nothing to a very big number very quickly -- that is, why does it look almost like one-half of a normal distribution?

The epidemic was started by theUSpresident. The Twitter profile says that this is the official parody account of the president of the United States. On February 3 theUSpresident had 38,000 followers. Each of the followers had signed up to receive all of the messages theUSpresident writes. So 38,000 people had access to the message. Assumption 2 clearly does not fit this case. The susceptible population turned out to be 6,500, but the number of potential contacts was 38,000.

One can go a step farther by looking at the followers of the individuals who retweeted the message in the first ten minutes after it was posted to Twitter. The messages was retweeted by 69 individuals. The number of followers ranged from 5 to 5418. The total was 22,793. Again the second assumption does not apply.

Why should one understand going viral in social media communication by looking at "#scariestwordsever President Palin"? Because that provides a process of spread in which there is no exogenous factor involved in the spread, i.e., assumption 5. If I had looked at reaction to the State of the Union Address or the stories about revolt in Tunisia or Egypt there would be many sources of the same message. But in this case there is only one and that is theUSpresident. So it is a relatively good fit to the assumptions with the exception of assumption 2.

This analysis shows something important about what may result in networks put together in 'cloud' infrastructure, such as Twitter or other social media, that differs from what is possible in a 'ground' network. On the ground human beings cannot get around to contact with thousands of other people. At least that is not possible in a brief period of time. But the cloud does not limit connections in the same way. One should note that 38,000 followers is quite unusual. Only a limited number of individuals have that many followers. But retweeting by individuals whose total followers is 22,000 is not unusual. That is common, which cannot be said for 'ground' networks.

There are at least 6 assumptions in the standard version of going viral. So the claim that a twitter stream is going viral is only an explanation if we are pretty sure the process is not too distant from the assumptions. But it is possible for going viral in the cloud to look very different from going viral on the ground because the constraints on contacts are very different in the two.

© G. R. Boynton, 2011