Twenty-four Hours Tweeting the State of the Union

G. R. Boynton

Forty-eight millions people watched president Obama's first State of the Union address the evening of January 27, 2010. [Gorman] In addition, the White House live stream went to 1.3 million. [Roa] But it was not all listening; microblogging was going like crazy, as well. In the twenty-four hours from 10:00 a.m. on the 27th through 10:00 a.m. the 28th there were 81,639 Twitter messages inspired by the address. [Boynton]

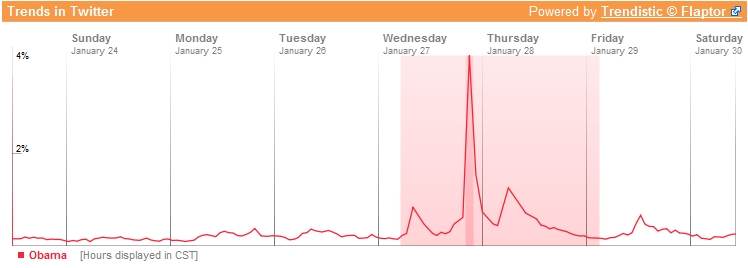

Eighty-one thousand may or may not be a large number. Twitter is new and we do not have very good standards for big and small. There are three pieces of evidence that suggest considering 81K a big number. First, when the Nobel committee announced that President Obama would be awarded the Peace Prize a virtual 'firestorm' erupted on Twitter. I collected just under 90K messages about the prize between October 9, the date of the announcement, and November 1. However, there were only 77K messages in the first 18 hours, which makes that spike substantially smaller than the one concerned with the State of the Union Address. Second, Trendistic reported the percentage of web messages for Obama at the height of tweeting about the State of the Union.

|

At the peak the messages about the State of the Union were 4% of all twitter messages. The same figure for the Peace Prize was just under 4%. The figure also gives a comparison of the spike with more ordinary tweeting about the president. From January 1 through the 26th the mean for percentage of all messages was 0.32%. The 27th spike was 12 times the daily average. Third, at some points during the speech all of the Twitter trending subjects were connected with the address. It was a big spike.

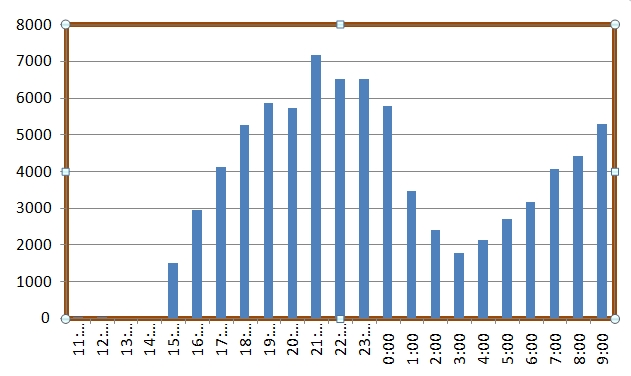

I wanted to examine the dynamics of the process -- what the messaging would look like over time. That was the reason for collecting the messages for 24 hours. This figure shows the number of tweets per hour.

|

The legend for the horizontal axis is the 24 hour clock. The number of tweets between 10:00 a.m. and through 14:00 p.m. are so small that they do not show in the figure. Beginning with 15:00 the number of messages increase every hour from 1500 to 3,000 to 4,000 to just under 6,000 at 19:00. The hour of the speech, 20:00, showed a very slight decline. Then a second surge began; up to over 7,000 the hour after the speech, and 6,500 at 22:00 and 23:00. After midnight the numbers decline to a low of 1,800 at 3:00 a.m. and then rise from there to just over 5,000 at 9:00 a.m.

The high point of twittering was not the hour of the speech. It was the three hours after the speech as the twitter universe produced a higher volume of reactions to what the president had said.

The hour the president spoke was also distinctive for the way individuals were tweeting. One hundred and forty characters is a very brief message. To ease this constraint conventions have developed to carry meaning with few characters. One of these conventions is the #hashtag; it is a word or an abbreviation preceeded by a #. In this case the hashtag used most often was #SOTU, that is, state of the union. However, many messages used the full "state of the union," or some simple derivative, in the message. During the 24 hours #SOTU was used 11,068 times and "state of the union" was used in 14,220 messages. That is only 35K out of 81K messages. This was messaging in the 'moment' such that the connection to the address could be taken for granted. The 'moment' was taken one step further. During the speech attention was so focussed on the speech that the abbreviation #SOTU could be assumed to be obvious. Before and after #SOTU may be somewhat less obvious. The result was

#SOTU |

State . . . |

|

| Before | 12.0% |

22.6% |

| During | 28.8% |

14.6% |

| After | 12.5% |

15.9% |

When attention was directly focussed on the speech the percentage of messages using #SOTU more than doubled and messages using state . . . declined.

One more convention illustrates the difference between the hour of the speech and tweeting before and after. Twitter messages frequently include references or pointers to other web documents. You can think of this being something like "did you see . . ." or this is the 'gist' and you can get the full story at . . . Messages about politics are more likely than others to contain these pointers that are embedded using http://shortened url. Since urls can be very long they do not readily fit in 140 characters, and a variety of systems, including Twitter itself, can shorten urls for the message. But the pointers all begin with http: so one can easily search for them. 39,891 were found in the 81K messages; pointers to web documents were found in 49% of the messages. When you look at the distribution before, during and after you find another indication that attention is focussed on the speech. Before 47.5% of the messages contained http:, during the speech only 9.6% contained http: and after the percentage was 53.3%.

These are three differences in the messaging before, during and after the address: 1) the number of messages surges after the speech, 2) the increase in the use of #SOTU during the speech suggests the focus of attention has narrowed to the speech, and 3) this is reinforced by the big drop in references to other web documents during the speech.

One reason to notice the difference is how it relates to sentiment assessment. CNN wanted to assess the balance of favorable and unfavorable messages during the address, and they put a crew of people to work reading and categorizing. [Simon] News Backdrop used a computer program for the same purpose. [News Backdrop] In both cases they assessed the reaction to the president's address by examining the tweets during the speech. There is certainly nothing wrong with what they did. But it does seem, looking at this evidence, that they produced partial accounts of the reaction to the address. The reaction did not get 'heated up' until the speech was over.

Nick Anstead and Ben O'Loughlin did similar research on microblogging during a particularly noteworthy BBC Question Time. They looked at reactions 'by the minute' to determine audience reaction to the discussion, and were able to show how twittering waxed and waned as the discussion changed. Unlike this study they found that microblogging declined quickly after the program was over. That may indicate something about either the 'enthusiasm' of U.S. partisans or about the perceived difference in importance of the two events. We will have to do more research to understand that difference.

References

Anstead, Nick and Ben O'Loughlin, February 2010, The Emerging Viewertariat: Explaining Twitter Responses to Nick Griffin’s Appearance on BBC Question Time (February, 2010).

Boynton, G. R., January 29, Tweeting the State of the Union

Gorman, Steve, January 28, 2010, Obama's latest speech seen by 48 million Americans, Reuters

News Backdrop, January 28, 2010, State of the Union -- Twitter Audience Reaction

Simon, Mallory, January 28, 2010, Social media on Obama speech mirrors Americans' frustration, CNNPolitics

Roa, Lina, January 29, 2010, Whitehouse.gov Streamed The State Of The Union Live To 1.3 Million People, TechCrunch

© G. R. Boynton, 2010

February 1, 2010