A Boynton Place

|

Watton Priory

We had stopped by to see what we could of Watton Priory. The cows were an unexpected bonus.

Watton Priory is a Boynton place. Sometime between 1160 and 1175 two daughters of Walter de Boynton joined the priory -- becoming nuns -- and Walter wrote a check to cover their tuition [A Boynton Story: You Want to Go Where?]. Watton is only about 15 miles from Boynton. So, Walter's daughters were not going very far away from home. The family would be able to visit them without difficulty.

Watton was a religious house of the Gilbertine order. Gilbert established the first religious house about 1140. Then about 1150 Eustace FitzJohn and his wife Agnes provided land in Watton to establish a priory there [A Boynton Story: Witnessing for God]. The Boynton sisters arrived just a few years later. They were close to being charter members.

|

The Place: Watton is a tiny village in the East Riding of Yorkshire. It's location on the map is identified by the hollow rectangle in the center of the image. Watton is, without disparagement, in the middle of nowhere. It is not close to Scarborough or Bridlington, which are on the shore toward the northeast. It is not close to Kingston Upon Hull or Beverley to the south. It is not close to York to the west. It is a tiny village sitting in the middle of rich farm land. It is possible to exaggerate the distance from all of these larger places, of course. The legend at the bottom of the map marks off 50 miles. It is not 50 miles to any of the places mentioned. Boynton is about 5 miles west of Bridlington -- approximately where the B is on the map -- and it is only 15 miles from there to Watton. There were hundreds, perhaps thousands, of tiny villages spread throughout Yorkshire. Boynton was an equally tiny village, for example. This was not a monastery in the middle of a bustling town. It was withdrawn from hustle and bustle by its location. The cows are an appropriate symbol of life in Watton.

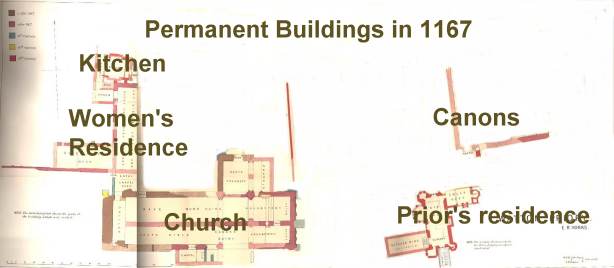

The Order: Gilbert of Sempringham established the order, which was the only native English order. It was started in Sempringham in Lincolnshire and most of the other houses were also in northern England. Many of them were in Lincolnshire and Yorkshire. Gilbert adopted and adapted the rules of practice of the Cistercians. They were particularly strict rules of conduct which he probably thought were required given the unusual character of the order. The most unusual feature of the order was that it included both women and men. Many of the houses were double houses including both nuns and canons. Watton priory included both, and that had a substantial impact on the buildings of the priory.

A good deal is known about Gilbert and his order. Brian Golding (1995) wrote a book specifically on the order. Raymonde Foreville and Gillian Keir (1987) translated, introduced and annotated The Book of St Gilbert. The Book of St Gilbert is the collection of documents that were submitted to the pope as part of the canonization of saint Gilbert. It describes his life, founding the order and its growth, controversies, and miracles. And Janet Burton (1999) covers the Gilbertine priories in Yorkshire in her book on religious houses in early Yorkshire.

However, not much is known specifically about Watton Priory. We know that its establishment at Watton was facilitated by the gifts of Eustace and Agnes FitzJohn. An early miracle is recounted by many sources including those listed above. There are a few additional charters. And the inventory when the priory was being closed by Henry VIII is available. In between the nuns, canons, and lay assistants went about their business of worship and service to the poor, and they did not make much news.

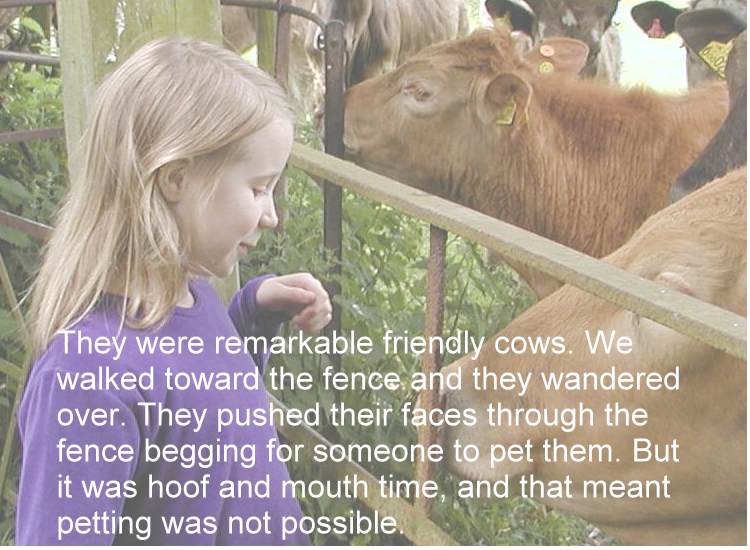

One piece specifically about Watton Priory is available. W. H. St. John Hope conducted an archaeological dig at Watton in the decade of the 1890s, and his report was published in The Archaeological Journal. The Archaeological Journal is not a widely available publication so we have included the paper here [The Boynton Library]. He begins with a brief summary of the rules of the order, but the primary focus is on what was learned about the buildings of the priory. He drew a reconstruction of the entire priory grounds based on his exploration.

|

The priory was surrounded by fields to the north [top of the image] and on the east and west. At the south there is a small creek. Across the creek is St. Mary's church, which is the parish church. It is still in use by the people living in Watton. The two large, black blotches on the map are the major buildings of the priory. The one on the west was the quarters of the nuns and the one on the right was the buildings of the canons. Hanging down from the building on the right is the residence of the prior, which still exists today. But this is the plan of the priory when it was closed in the sixteenth century imposed on an Ordnance Survey map -- there probably were no railroad tracks in the sixteenth century or earlier.

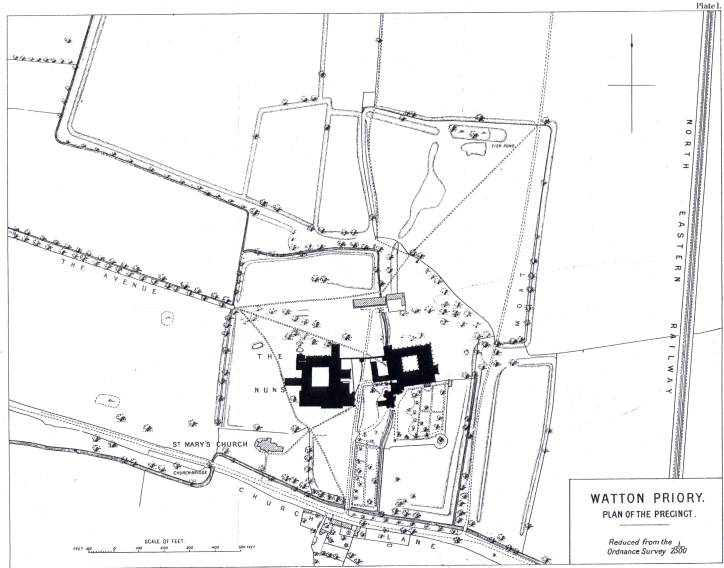

Living at Watton: When the Boynton sisters arrived at Watton they saw something that looked a bit like this. The priory was only fifteen or twenty years old, and the building had only started.

|

First things first -- the church was already built. Even though it burned down in 1167 it was rebuilt using the same plan. One of the rules of the order was -- no touching, no talking, not even seeing. The men and women were to live in close proximity, but there was to be no interaction between the nuns and the canons. The church was divided down the middle with the nuns worshiping on one side and the canons worshiping on the other.

|

The sacrements were administered by the canons to the nuns using a turntable that passed the elements but prevented sight. St. John Hope drew a version of the turntable looking down on it. The round turntable would spin, and the crossing pieces would prevent sight even as it was spinning. The only time the canons were to interact directly with nuns was when the nuns were dying and in need of unction and the last rites of the church.

Eventually a wall would be built between the nuns' compound and the canons' compound to match the wall in the church. But that would not be done until later in the thirteenth century. The Boynton sisters probably did not live to see the wall go up.

The prior's residence was also already built. In keeping with the double nature of the priory there were double administrations. There was a prior who was a man and who had primary responsibility for the canons. There was a prior [or prioress] who was a woman and who had primary responsibility for the nuns. It is worth noting that the prior, who was a woman, did not in 1167 and did not later have a separate residence even though she would have had one in a priory only for nuns. Gilbert established his order to make it possible for women to follow the religious life, but the normal hierarchy in governing seems to have been followed.

When the sisters checked in they were issued their uniforms.

Each nun had five smocks, three for labour, and two cowls for use in cloister, church, chapter, frater, and dorter; also a scapulary for labour. Each had further a pilch of sheep's wool, and a chemise of thicker stuff, if she wished, with a linen herchief dyed black and furred with lamb's wool. All headgear was to be black and thick, as were also their veils. [St. John Hope, pp. 5-6]

Work and worship was the life of the members of the priory, and Gilbert established the division of labor. The canons were responsible for the finances, which was mostly farming, and the women were responsible for food, washing clothes, and other female tasks. The kitchen was already in place. It was to serve both the nuns and the canons, and the nuns were to be responsible for its operation.

There must have been temporary buildings in addition to the ones that St. John Hope could find in his digging. He could find footings and some walls, but temporary buildings would have been torn down and replaced with later stone buildings. Even in 1167 there must have been more buildings than those pictured because there is no place for the canons to sleep in this construction. There was also no cloister and no chapter house, which were standard parts of a priory.

The miracle: The place was all abuzz. Either shortly before or shortly after the Boynton sisters joined the priory the miracle was all that anyone there could talk about. Of course, talking was carefully circumscribed.

Miracles were standard practice in sainthood; saints performed miracles. That was one of the ways you recognized a saint. However, this was one miracle that Gilbert and his followers were not proud of; it does not appear in The Book of St Gilbert. It does appear in correspondence of Aelred of Rievaulx who Gilbert called on for advice about dealing with the miracle. The letter written by Aelred is all that we know about the miracle. Everyone who recounts the story is working with the same letter. One version of the story is by Frederick Ross (Ross, pp. 181-188). It is a fully developed version of the story. Giles Constable does a thorough historical analysis of the story, the people involved, and how it should be understood in the context in which it happened (Constable, pp. 205-226)

Elfleda was her name, and her sponsor was the Archbishop of York. He asked the priory to take her in when she was only four years old. She grew up. There was no wall between nuns and canons -- as far as we can tell from St. John Hope's digs. She saw one of the lay brethren, fell in love, and conceived a child. Her violation of the rule became obvious to all. The young man was punished and chased away. Elfleda was punished. As the time of birth approached the archbishop, now dead, appeared in the night took the unborn child and cleansed her of her sin. It was a miracle.

It was a miracle to keep the priory buzzing for years.

And that is the last story about the priory that anyone knows. St. John Hope traces the development of the priory by dating the structures that are left. But they were very quiet for about four hundred years.

Today: St. John Hope dug up the footings, some walls, and other remnants of the long forsaken priory. Then he covered them up again; they are buried. If you visit Watton today you see cows. If you look beyond the cows into the field you see bumps, which seem to be left after covering walls and footings.

|

And if you look beyond the cows you can see a bit of the prior's residence, which has been a private residence since Henry VIII closed down the priory in the sixteenth century.

|

What you can see -- without peering through trees -- is the parish church. The brief history of the church indicates that it was built in the late sixteenth century or early in the seventeenth century.

|

The oldest and most interesting piece of history in the area is the stone slab monument to William de Malton dating from 1279. He was the prior of Watton, and this was carved at his death.

|

There is a second person in the picture to give an indication of the scale of the stone monument. Prior Malton seems to be just over one head taller than a contemporary eight year old.

As we left we read a sign posted on a fence post -- tea room to be built. Perhaps they are going to dig up some of the priory to attact tourists.

....

Burton, Janet (1999) The Monastic Order in Yorkshire, 1069-1215, Cambridge University Press.

Constable, Giles (1978) Aelred of Rievaulx and the nun of Watton: an episode in the early history of the Gilbertine order, in Derek Baker, ed. Medieval Women, published for the Ecclesiastical History Society by Basil Blackwell.

Foreville, Raymonde and Gillian Keir (1987) The Book of St Gilbert, Clarendon Press, Oxford.

Golding, Brian (1995) Gilbert of Sempringham and the Gilbertine Order c. 1130-c. 1300, Clarendon Press, Oxford.

Ross, Frederick (1892) Legendary Yorkshire, Hull.

St. John Hope, W. H. (1901) The Gilbertine Priory of Watton, in the East Riding of Yorkshire, The Archaeological Journal, vol. lviii, pp. 1-30.

|