Surviving Bannockburn

It's time. The taxes have been collected. The draft boards for the northern counties have been appointed. We are going to assemble a massive force and destroy the Scottish rebels. Terrorists! That's what they are. It's my kingdom, and Robert the Bruce is stealing it. Well, not much longer.

So it started. The writ went out. "You will join king Edward II at Berwick-upon-Tweed to march upon the Scots." And it was a mighty force -- twenty thousand strong and almost four times the size of the force that Robert the Bruce would be able to assemble (McLaren, p. 125).

The Boyntons were among the king's 20,000 men. Robert had been involved in the planning for a long time. He had served in the parliament that approved the taxes, he collected the taxes, he had been on the commission of array -- the fourteenth century draft board [A Boynton Story: Department of Defense 14th Century Style]. John, Robert's son, as well as Edmund, Robert's compatriot, were also among the troops. So was Ingram, lord of Acklam, Roxby and Leaventhorp. The Boyntons of Boynton were there. The Boynton Triangle Boyntons were there. Off they went to war.

The Story Line

The story goes like this: Stirling castle was besieged by Edward, brother of Robert the Bruce. Edward II called for a force, met them at Berwick and hurried them toward Stirling castle as quickly as they could manage. At Bannockburn, several miles short of the castle, they encountered Robert the Bruce and the Scottish army. The first day there was a skirmish between an English calvary troop and one wing of the Scots; the English were soundly defeated by the Scot's schiltron. Philip Mowbray, the English commander of the castle, rode out to meet the English army to consult with Edward. The second day the two armies joined in battle. The English were ignominiously routed, many died, and the rest headed back to England on the run.

There are no contemporaneous accounts of the battle. The accounts that survive were written by authors who were not there and they were written 25 to fifty years after the event. There are no records of the battle in the records of Edward II, and there are few records of expenditures or lists of participants. All of the historians who have written about the battle have the same documents available. Mackenzie (1913) and Morris (1914) wrote early in the twentieth century. McLaren (1964) wrote in the middle of the century and Nusbacker (2000) wrote at the beginning of the twenty-first century. While their accounts differ in many ways there is quite general agreement on the story line.

The Rationale

For some years Robert the Bruce had been taking troops into northern England and raising money by threat, ransom, and thievery. In Scotland he was attacking, capturing and

|

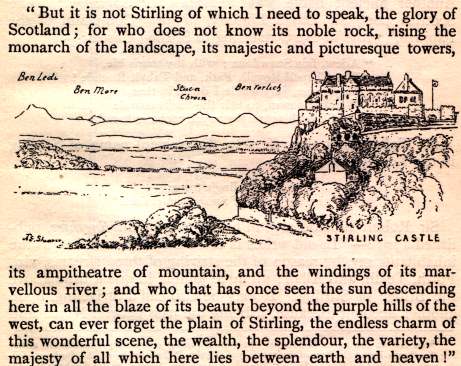

| Stirling Castle, Shearer's Illustrated Historical Guide |

destroying the castles that were English strongholds. Stirling castle was besieged, and did not stand much chance of holding out against Edward, Robert the Bruce's brother, and his men. However, the Scots would surely be defeated if an English army arrived to save the castle. So Mowbray, the commander of the castle, and Edward made a deal. The English soldiers occupying the castle would not be disturbed -- captured, killed -- for a year. If an English army arrived within a year, by the end of June, 1314, the Scots would lose the castle. If an English army did not arrive within the year the English would relinquish the castle without a fight.

The end of the year was drawing nigh, and that deadline hurried the recruiting and the march on Scotland. However, it became clear that this deadline was more an excuse for action than what Edward II hoped to accomplish. He wanted to fight and destroy Robert the Bruce and his army of Scots. That is what he hoped to do in the process of re-taking Stirling castle.

The Armies

The estimates are, at best, very rough. Contemporary historians agree that the estimates of the original writers were greatly exaggerated. Everyone is confident that the English army was somewhat larger than usual for English medieval armies. And everyone seems satisfied that the English army was four or five times as large as the Scots.

The estimates for the English army range from two to three thousand knights and between fifteen and twenty thousand foot soldiers. This required hundreds of carts to carry the supplies for the soldiers and animals. The English lords did not give up much comfort on the trip, however. The king, for example, carried a wine cellar with him. The army was led by the earls of Gloucester and Hereford who had difficulty cooperating. Two leaders who cannot bring themselves to cooperate is not exactly the way to run a war.

The Scots had only a small calvary. The estimate is about 500 knights. And they had about 5,000 soldiers on foot. Many of them had fought with Robert the Bruce earlier as he led skirmishes through northern England. Robert the Bruce was in charge, and he had three commanders, including his brother, with whom he had fought in the past.

With a four or five to one advantage the English should have wiped out the Scots -- or so say the historians. That is not what happened, however.

The Skirmish: June 23

When the English arrived at Bannockburn the Scots were already there. They were positioned in a heavy wood where the English could not see them. They had been there for weeks preparing for the English. Mowbray, who was in charge of Stirling castle, hurried out to meet the English to tell the king what he knew about the Scottish army and their preparations. He suggested that the arrival of the English army was sufficient for the deal he had made with Robert the Bruce's brother. It was not sufficient for Edward II, however. He sent a troop of knights to explore one of the routes to the castle. He intended to fight -- not just occupy a castle.

The Scots were on foot. The English were on horse. The Scots used a formation of the men on foot, a schiltron, to protect themselves from the knights on horses. The schiltron was a circle of soldiers facing outward -- each with a fifteen foot spear. It was 360 degrees of soldiers with spears locked together. Inside the circle were replacements: replacement soldiers and replacement spears. If a soldier fell he was replaced by someone inside the circle, and if a spear was broken it was replaced from the center. When the knights charged the circle of foot soldiers their horses were speared and wounded or killed. The knights could not get close enough to the foot soldiers to do much damage. After futile assaults the knights took their wounded or killed companions and beat a retreat.

For the Scots the news was very good. They had defeated mounted knights -- very handily.

The Battle: June 24

The next morning the English troops prepared to attack the Scots if they could find them. They did not expect Robert the Bruce to fight on an open field. Bruce had led raids against northern England for a number of years, and when the English armies had tried to engage him the Scots melted away. But this day was different.

The vanguard of the English troop was led by the earls of Gloucester and Hereford with their men. They were knights on horse ready to charge the enemy. This was the prestige point of the army because it meant you got to attack first. There were eight battalions behind the vanguard ready to charge after the vanguard. The Scots left the woods and formed themselves into three large schiltrons with a fourth led by Robert the Bruce prepared to act as required as the battle developed.

The English knights charged. The result was the same as the day before. The horses were speared. Knights fell and were immediately attacked by the Scottish foot soldiers. But knights in the following battalions kept pushing forward. Horses were speared and lay dead or injured on the turf or turned back in confusion. It was a bloody mess. The knights at the front of the force were being slaughtered by the schiltrons of the Scots and their own troops kept pushing them into the Scots to be slaughtered. And the earl of Gloucester, who had been in charge, died in the first charge.

Plausible Deny-ability

Unlike today, medieval kings led their armies. Kings were warrior princes. A king could not leave the scene of battle -- even if things were going very badly. That would put a big chink in his reputation as feudal warlord. So there were knights who had the responsibility of escorting the king from the scene -- the king protesting all the while that he really preferred to stay and lead his men.

Not very far into the day it became clear that if the king stayed much longer he was going to be in great danger of being captured by the Scots. His army was foundering, and very shortly they would melt away. So the earl of Pembroke and sir Giles de Argentine led Edward II from the field of battle -- eventually to safety by returning to England [Nusbacher, p. 142].

Edward II could always say that it had been Pembroke and Giles de Argentine who made him leave the battle -- plausible deny-ability is what we call it today.

Surviving Bannockburn

Knights were slaughtered by the Scots. Their horses were no match for the schiltrons. The English archers who could have decimated the schiltrons were cut off. And the English troops kept pushing and pushing from the rear.

But we know the Boyntons survived this bloody battle. We know because there are documents with later dates bearing their names. How did they do it?

How the Boyntons survived is very much a function of the way the battle was fought. The terrain that could be used for fighting was quite narrow. The English army could not spread out across a battlefield. Instead most of the force was lined up -- many deep -- behind the vanguard. Those in the rear had no opportunity to fight except by pushing forward, which they did too much of.

The earls of Gloucester and Hereford made sure that the vanguard was populated with their men who they could lead into battle. Yorkshire knights were back in the pack -- with the king who was also back in the pack.

Back in the pack was a safe place to be. When the king was being led away it became clear that the day was lost and the best thing to do was head back to Yorkshire just as fast as your horses would take you -- which is what they did.

And they lived to tell the tale -- though they never wrote it down, unfortunately. So, this is a surmise since they did not leave a record. We know they were there. We know they survived. It must have happened something like this.

Remember the Alamo

The battle of Bannockburn was 1314. That is some time ago. Why are people still writing about it?

If you grew up in Texas you would have learned "remember the Alamo" from your earliest years. That was a defeat, of course. But it became an identity producing war cry. Suddenly there was a Texas and a slaughter to be revenged -- an honor to be redeemed.

Apparently Remember Bannockburn works the same way. It was the major victory of the Scottish armies against the English. And it seems to be Scots who still write about it -- it still calls forth an identity.

But it was not a notable day in Boynton family [or English] history.

....

Mackenzie, W. M. (1913) The Battle of Bannockburn; a Study in Mediaeval Warfare, Macmillan and Co.

McLaren, Moray (1964) If Freedom Fail; Bannockburn, Flodden, the Union, Secker & Warbrugh, London.

Morris, John E. (1914) Bannockburn, Cambridge.

Nusbacher, Aryeh (2000) The Battle of Bannockburn, 1314, Tempus.

Shearer, Robert S. (1897) Shearer's Illustrated Historical Guide to Stirling, Stirling Castle, Bannockburn, Wallace Monument, and Neighbourhood, R. S. Shearer & Son.