Arab Spring From the Ground Up

G. R. Boynton

February of 2011 became Arab spring.

'Arab spring' was born in 2005 when Republicans argued that the US invasion of Iraq would lead to the flowering of democracy throughout the entire region. It did not happen and Arab spring was retired. Retired until 2011 when, instead of the flowering of democracy, revolt against tyranny spread across the entire region. First Tunisia, then Egypt, then Bahrain, then Libya, then Syria, then Yemen, and on. And the language of Arab spring was reborn.

It was Arab spring in the spring, and in the summer and in the fall and in the winter and in the spring of 2012 where it continues to be used as in this headline of theguardian "Arab spring leads to wave of Middle East state executions." (Dehghan and Pilkington) Just as it was used in the mainline media it was also used in the new media. Specifically it was used quite frequently in messages posted to Twitter.

This is a paper about cultural construction in the language of Arab spring. The new media often involve cultural construction. In a paper about the shooting of Representative Giffords, of Arizona, we showed both the extent of using Twitter to communicate about this event and how it became communication about the appropriate boundaries of political discourse. (Boynton and Richardson, 8/27/2011) In a nation where freedom of expression is important negotiating the boundaries of appropriate discourse can hardly be done by law and must be done in the interplay of language in use and critique of the language used. The discourse that was challenged was: a target planted immediately over the map of congressional districts, the slogan don't retreat, reload, and support for an opponent who had campaign events at a rifle range for M16 practice. The argument revolved around the way such campaign discourse fostered or did not foster individuals to take up direct action. In a paper about #OccupyWallStreet I show how the language of the movement evolved during its initial phases to constitute an identity that became a noteworthy part of American and global politics in 2011. (Boynton, 10/9/2011) In language cultures are constructed.

In this paper I examine the use of Arab spring to determine the way it was used in the history of Spring 2011 through the end of the year. This is a search for cultural construction and cultural pentration. Our language implies they should be found.

Data and Methods

I assembled two sets of data for the analysis. I collected Twitter messages that mention Arab spring beginning in April of 2011 and running through the end of the year. Simultaneously I was collecting Twitter messages that mention #Feb14 (the hashtag for the revolt in Bahrain), #Libya, #Syria, and #Yemen, which were the nations in which citizens rose in revolt against tyranny during the spring.

To collect these Twitter messages I used Archivist. It is a desktop program running under the Windows operating system. It queries Twitter at five minute intervals for the search term it is given and adds the Twitter messages it finds to a file it constructs for the search. It will export the file to a tab delimited format for further analysis. I ran the program 24 hours a day, seven days a week for the entire period, which is somewhat different for each country since their revolts did not start at the same time. The searches for $Feb14, #Libya, #Syria, #Yemen, and Arab spring were independent searches with the results from five searches used to create the data files for analysis. The data used in the paper is close to being the complete set of messages for the period. There are two caveats. Very infrequently one or another of my computers malfunctioned. The loss is very small, but it did happen. Two, Twitter will supply only 1,500 messages per search request. That means the program cannot collect more than 18,000 messages per hour. That limit was exceeded only very infrequently, but it is also a source of a small loss of data. The limit to the most recent 1,500 messages also means there is no history. Either you are there when the messaging starts or you have no access to the older Twitter messages. I started collecting Twitter messages containing Arab Spring April 20,2011, and I cannot obtain tweets earlier than that.

The analysis is simple. It is a series of counts for changes over time and interactions between the collection of data files.

The argument

I am going to argue that Arab spring is largely a western construct that was not taken up in the countries in which the revolts were occurring . That it never did become from the ground up. First, I will suggest how it became important to western observers. Then I will turn to its use in the countries of Middle East and North Africa.

Arab Spring

The term 'Arab spring' arises in the spring of 2011. My collection of Twitter messges began on April 20, but it was being used before that date. I cannot access the Twitter messages, but I did check with Google Real Time to determine the frequency of Arab spring as a query. The figure shows the time line for queries from the first of January through about half of May.

|

Google does not supply numbers; one gets only the relative distribution over tiime. It is clear from the figure that Arab spring was not a term used in queries with any frequency in January or February. Only in March does the use begin to climb and then it becomes much more frequently used in April and into May.

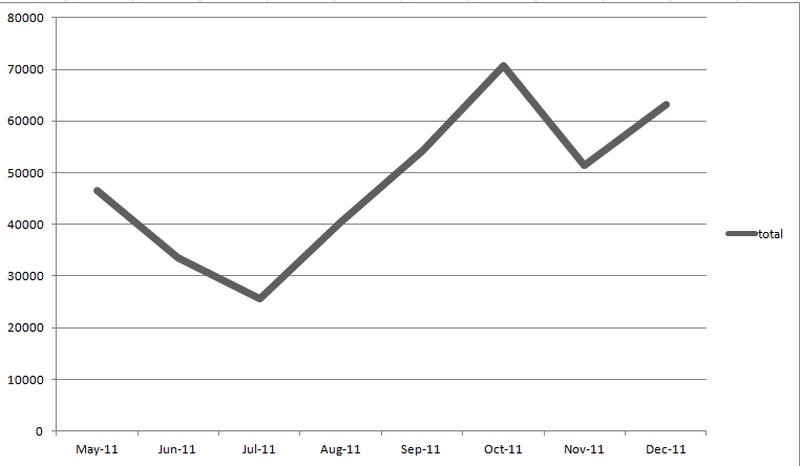

The Twitter messages I collected containing Arab spring, aggregated by month, are displayed in the next figure.

|

Arab spring was used almost 50,000 times in May, but use fell during the summer. Then in September it rose to appear in 54,000+. It hit 70,000+ in October and then fell back slightly in November and then climbed again in December. By the end of the year it had gone from almost nothing in January, as best we can tell, to over 60,000 messages per month. Sixty thousand is a large number; on average it is 2,000 messages mentioning Arab spring a day. But it is difficult to assess this quantity without a suitable frame of reference. For December the number of Twitter messages mentioning #Feb14 was 270,398, mentioning Libya was 112,983, mentioning Syria was 1,330,340, and the number mentioning Yemen was 179,471 for a total of 1,893,192. Sixty thousand is a large number of messages using Arab spring, but it is not large relative to the total discussion of the revolts in the four countries.

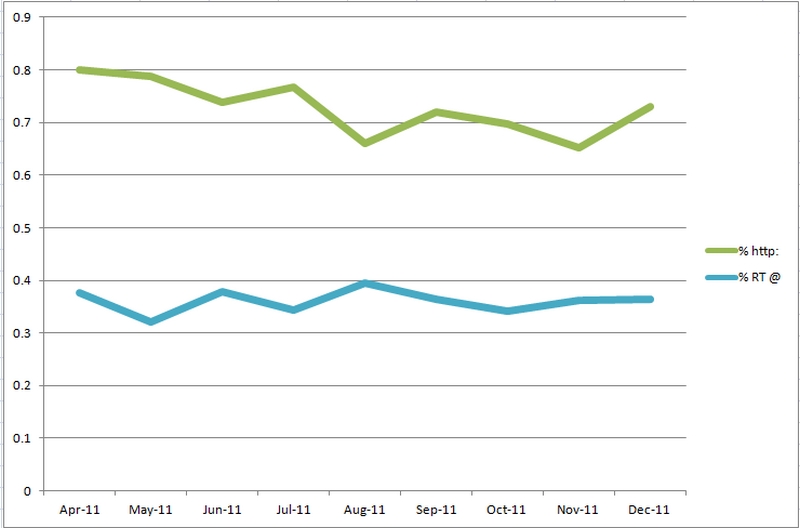

Two features of the messages suggest what the communication was. The first is the relative number of urls and retweets.

|

The figure displays the percentage of messages in the Arab spring collection that were either urls or retweets by month. While not completely straight lines there is considerable stability in the distribution through time; much more stability than in total messages. The number of messages was a long term trend upward with declines and surges through the months. When either rising or falling the percentage of messages that contained urls or retweets was close to constant. They are a standard feature of the message stream even as the stream itself fluctuates.

As generalizations a Twitter message including a url can be understood as a 'news move' (Boynton, 10/20/2011) and a Twitter message including a retweet can be understood as a 'we move.' (Boynton, 12/12/2011) The news move is "did you see that . . ." and a reference to a reference document. In political messaging the reference document is almost always a news report. Some of the news reports are mainline media publications and some are internet publications. But these messages are almost always calling attention to something beyond themselves, to news.

The 'we move' is about constituting a community of feeling and action. I have shown the importance of this in the inception of the revolts. (Boynton, 3/14/2011) Retweets were also important in building a community in the Occupy movement. And they are important in response to something as distant from major social movements as the shooting of a young black man Trayvon Martin. On one day, March 23, 2012, there were 17,000 messages inviting others to join in fighting against racism by retweeting. For each retweet a dollar would be donated to a foundation to fight racism. It was a call to identification with the horror of the shooting and action to reduce the chance of it happening again. It was a we acting together.

The difference in the use of urls and retweets in messages containing Arab spring is an important indication of what the communication was. In one month as many as 80 percent of the messages included urls and in all but two of the months the percentage of messages containing a url was below 70 percent. This is a stream dominated by the news move. It is "did you see that . . ." over and over.

If the messaging was about the news how did the nations of the area figure in these comments?

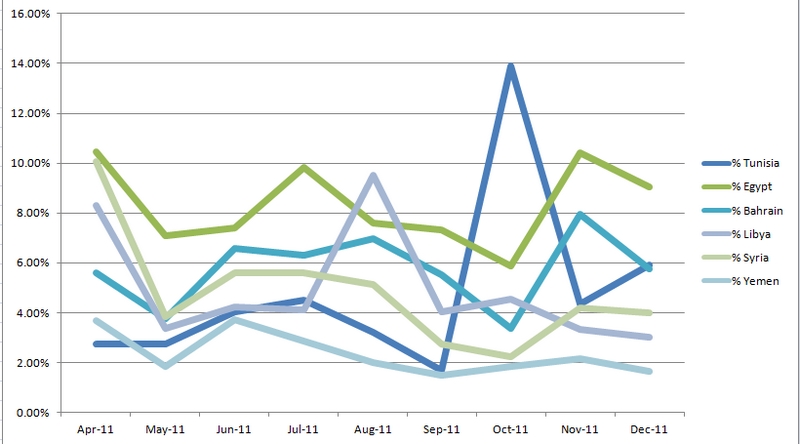

|

I counted the number of times Tunisia and Egypt, whose revolutions were already over, and the four countries were mentioned each month. The figure shows the percentage of Twitter messages in each month that included one of the countries. The figure is very crowded, and that is really the point. There was very little difference in the mentions from one country to another and from one month to the next. The range is only between two percent and ten percent with one outlier at 14%. Egypt was thought to be the touchstone for the subsequent revolts. It is the most prominent of the countries and the revolt there showed that dictators could be replaced. While Egypt is mentioned more frequently than Yemen, for example, the range is between six percent of the Twitter messages in one month and 10 percent in another. To the extent that it was news about individual countries the news was scattered between them with little dominant focus.

If the focus was calling attention to and commenting on the news but there was little focus on the countries involved how should one interpret the use of Arab spring?

One, it was a conceptual simplification by holding together disparate reports from six different countries. You could imagine that there was a single process going on into which each individual piece of news would fit. But it did not fit into a coherent account. The military in Egypt acted one way and in Libya they acted quite differently. The governing family in Bahrain was supported by troops from Saudi Arabia, but there were no neighboring troops for Yemen. Schisms between Sunni and Shia were important in Yemen but not in Bahrain. So the news was held together by the very general conception that revolt was occurring. Each bit of news was about individual acts of revolt, but the pattern of the revolts were dramatically different from one country to another.

Two, Arab spring satisfied two constraints for number of characters. One, aTwitter message can be no longer than 140 characters. There is no room to enumerate all six country names: Tunisia, Egypt, Bahrain, Libya, Syria, and Yemen. By the time you had finished you would be more than a third of the way through the number of characters available. For Twitter messages one needs linguistic shortcuts. And that is as true for people calling attention to the news as for individuals telling about their latest purchase or expressing their admiration for an entertainment figure. Two, it also satisfied the constraint for news media headlines. Headlines have to be pithy. They must in a few words convince you that you want to read the rest of the story. Arab spring was both a brief phrase and in use it captured the conception that there was one process going on there, and one would want to read about the latest episode in the working out of the process.

Three, there is a certain romance in Arab spring. Compare that to one alternative -- MENA, which is short for Middle East and North Africa. Acronyms go well in bureaucratic organizations, but they have rarely been accused of romance. MENA is a short cut without the 'vibes' of Arab spring.

What about in the Twitter messages specifically mentioning the countries?

Twitter communication about Bahrain, Libya, Syria, and Yemen

Arab spring rolls off the tongues of western observers. We know what it is; we know what it is about. If Arab spring is about anything it is about Tunisia, Egypt, Bahrain, Libya, Syria and Yemen. They are the ground of Arab spring. So what is Arab spring in its ground?

Arab spring burst upon the world early in the spring of 2011, and it increased in use through the year. If it had become an important element in the communication about the countries it should have become that by June. I am going to examine the use of Arab spring in the Twitter messages that were captured between June and the end of 2011 that refer to the revolts in Bahrain, Libya, Syria and Yemen. As I noted for December the number of Twitter messages is very large.

Bahrain |

Libya |

Syria |

Yemen |

|

| June-December | 1,865,740 |

,2,818,209 |

7,181,818 |

1,378,385 |

The range is from 1.4 million referring to Yemen to 7.2 million mentioning Syria. This is a huge outporing of messaging and it was accompanied by marches and protests demanding the end to tyrants. This communication, whether via social media or in their protests, is what the world has responded to with the phrase Arab spring, with admiration and some assistance.

Arab spring might exist as a common bond between countries as they share their ambitions for freedom from tyranny. The bond might not be communicated with the phrase adopted by Western observers, but it might exist in cross references. A Twitter message about Bahrain might also mention Libya or Syria or Yemen. Their shared desire and shared fate might be communicated in this type of cross referencing. So it is not enough to look at the incidence of Arab spring. It is also important to look at the cross referencing in the Twitter messages.

The table is percentages of messages mentioning Bahrain, for example, that also include Libya, Syria, Yemen and Arab spring.

| Bahrain | Libya | Syria | Yemen | Arab Spring | |

| Bahrain | 0.05 |

0.05 |

0.18 |

0.055 |

|

| Libya | 0.009 |

0.127 |

0.115 |

0.044 |

|

| Syria | 0.009 |

0.13 |

0.208 |

0.04 |

|

| Yemen | 0.02 |

0.055 |

0.037 |

0.02 |

|

| Arab Spring | 0.049 |

0.016 |

0.008 |

0.03 |

The table must be read 'down.' The column headed by Bahrain gives the percentages of messages mentioning Bahrain that referred to the other countries and Arab spring. These are very small numbers. Less than one percent of the messages mentioning Bahrain also mention Libya or Syria, and only two percent mention Yemen and five percent mention Arab spring. Bahrain is the most isolated of the nations. But the cross referencing between the other nations is not much higher. While Bahrain has the fewest cross references Yemen has the most. The numbers are 18%, 11% and 21%, but Yemen has the fewest mentions in messages referring to other countries with two percent, five percent and four percent. The only pair which has larger reciprocal references are LIbya and Syria. Messages about Libya also refer to Syria 13% of the time, and messages about Syria refer to Libya 12.7% of the time.

Conclusion

What should I make of this? What is a reasonable conclusion?

Twitter messages are a reasonable index of attention to a subject. Right now, for example, the number of Twitter messages mentioning Syria is roughly 100,000 per day. That adds up to three million a month. And Libya is down to a few thousand per day. That surely reflects the attention that the two countries are attracting. Libya is 'over' and Syria is still killing its citizens. It is also possible to note surges and declines in message streams. (Boynton, 3/23/2012) But there might have been more than that here.

When I started the project I was confident that the stream of messages identified by Arab spring were quite different from the message streams identified by the hashtags for the country revolts. I believe characterizing Arab spring as a western construct is appropriate. There is one more bit of research that would add to the counts I have made. I could go through the names of authors of those Twitter messages getting the balance of western and Arabic names.

I am not as confident in my characterization of the messages defined by hashtags for the country revolts. The cross referencing is very modest. That is certainly not unexpected. If you are protesting in Bahrain you chief concern is going to be what is happening 'on the ground.' How to organize. How to avoid persecution. How to bring enough pressure to bear to bring about change. What happened in Egypt may give you hope, but it did not work the way Bahrain is working. But I may be identifying quantity and importance in a way that is not illuminating. I remain puzzled about the results.

References

Boynton, G. R. (3/23/2012) Triggers and Surges

Boynton, G. R. (3/14/2011) Twitter and the Inception of Political Revolts

Boynton, G. R. (12/12/2011) The 'We Move' in #Occupy . . .

Boynton, G. R. (10/20/2011) The 'News Move' in Twitter Messaging

Boynton, G. R. (10/9/2011) Noticing Identity in Social Movements -- #OccupyWallStreet

Boynton, G. R. (3/14/2011) Twitter and the Inception of Political Revolts

Boynton, G. R. and Glenn Richardson (8/27/2011) The Language of Threat in Our Political Discourse

Dehghan, Saeed kamali and Ed Pilkington (3/26/2012) Arab spring leads to wave of Middle East state executions, theguardian.

© G. R. Boynton March 28, 2012