Politics Moves to Twitter: How Big is Big and Other Such Distributions

G. R. Boynton

University of Iowa

It's only 140 characters. Why should any political scientist pay attention?

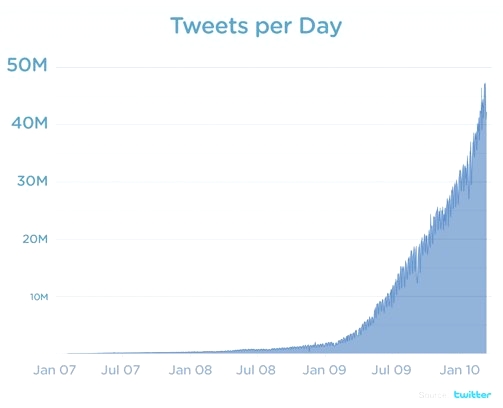

First, it is communication that is by default public. Hence, almost all of the messages are addressed to a public audience, quite literally the world. There will have been more than 12 billion twitter messages before this paper is read, there are now 50 million messages a day [GigaTweet]. And it is 'growing like a weed.' This figure from Twitter shows the growth curve of messages per day [Marshall Kirkpatrick].

|

During the primaries and the election of 2008 a lot was made of the Obama campaign's effective use of Twitter and other social networks. He had more than a million followers on Twitter. Look at the figure for that time period. It looks like almost no action relative to what comes after. By January 2010 it was almost up to 50 million per day, but it is flying past that number. It is hard to know how to describe something changing this rapidly. Only about forty percent of the messages are in English. So this is a global phenomenon. And most of the messages are not about politics. Unfortunately we do not know how many are about politics. I am going to show that there are a great many, but a reasonable count of total political messages is probably infeasible.

Second, there is a great quantity of political messaging on Twitter. Teaparty, for example, is a roiling social-political movement that is almost wholly on the web. It has no offices. It has no officers. There are a few websites and one or two social networks. But Teaparty is first and foremost #teaparty, which is a way of identifying messages that are about the movement. I have captured 400,000+ messages identified by #teaparty between December 8, 2009 and March 5, 2010. This is becoming an important movement in US politics, and it is almost all online; Teaparty is just #teaparty, to exaggerate a bit. One other stream of messages illustrates the point of the growing incidence of politics in messages on Twitter. The passage of health care reform was long and hard. There were a number of streams of messages connected with it. Far and away the largest was #hcr. Between November 14, 2009 and May 5, 2010 there were more than 580,000 messages identified by #hcr. And it had the largest one day total I have captured with 99,000 messages on March 22 at the height of the action that produced health care reform. These are huge streams of messages about important events of politics, both U.S. and global.

Conceptual Starting Point

My theoretical underpinning for studying this political communication is fourfold.

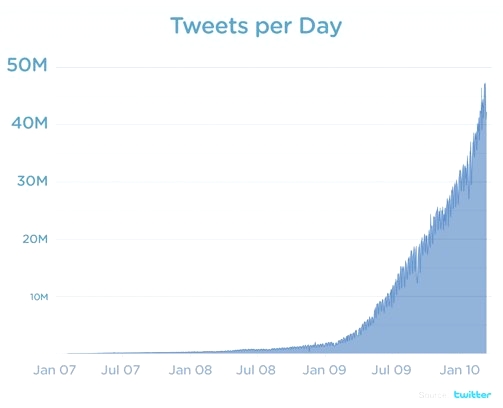

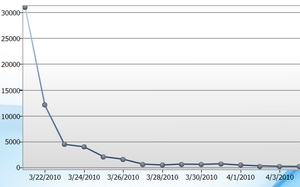

One, this is political action; it is not about audience. We have studied political communication by examining mass media as the communicators and using surveys to identify what we, the audience, are taking from the messages presented to us. There is a huge literature examining what the mass media presents. And the Pew Foundation with their news interest index [Pew Foundation] is now giving us the best studies of audience we have. Users of Twitter are communictors, and they are communicators even when they are audience. One example of this is the message stream surrounding President Obama's 2010 State of the Union Address [Boynton, February 1, 2010]. I began collecting twitter messages at 10:00 a.m. the day of the address, and continued by searching at 5 minute intervals until 10:00 a.m. the next day. The figure shows the distribution of messages per hour for the 24 hours.

Figure 1. Messages per hour for 24 hours around State of Union |

|

The x axis of the figure is a 24 hour clock. The number of messages before 14:00 p.m. is so small that they do not show on the figure. Then the messaging builds up through 19:00, but at 20:00, which is the hour of the address, the messaging decreases slightly. After the address is over the messaging picks up. By 1:00 a.m. the messaging begins to fall, the nadir is 3:00 a.m., but then it picks up again. The morning after there are still three to five thousand messages an hour. This is not audience. It is people communicating about the address before, during and after. The mass media have to 'move over' as they become only some of the streams of communication about important political events.

Two, I am interested in streams of messages. These are not disconnected bursts from atomized individuals. By using conventions that have been developed by users of Twitter the messages are connected. If you wanted to address people concerned about health care reform in the U.S. you included #hcr in your message. You searched for and read messages that included #hcr and you expected that others were doing the same and that your message would reach this audience of concern. And #hcr was used by people with many different views about what health care reform should be -- including those who were delighted with the proposals that eventually became the legislation as well as those who wanted to stigmatize those proposals as marxism. These are streams of messages 'making the case' of one sort or another. Microblogging is the acropolis of the twenty-first century or, at least, the first years of the century.

Three, these are opinion leaders of society. We have known since Lazarfeld et. al. in the 1940s and then Katz and Lazarsfeld (1955) that the conception of communication as produced by the mass media and picked up by the audience is a gross oversimplification that reveals less than it hides. They called it the two step flow of communication where the second step involved opinion leaders who are the persons most engaged in social communication about politics or fashion or sports or any of the domains of communication. They are experts for their less engaged friends and they structure the flow of communication by calling attention to some and ignoring others and by framing the communication in one way and not in others. The active users of twitter are almost by definition among the more actively engaged individuals in communication in society. The two step flow is difficult to study because it does not fit naturally into random sample surveys. In the 1980s Huckfeldt and Sprague began researching networks of communication that revealed much about the connection between mass media and the conversations of citizens [1987]. But twitter offers a new way to effectively conduct research on opinion leadership. One of the structural features of a twitter account is the ability to follow other twitter users. And there is a public record of the number of people who receive the messages of or follow persons writing the messages. For example, in early March 2010 Sarah Palin announced that she and her family had used the Canadian single payer health care system. Since that seemed at odds with her then current claims about a single payer system it became a very small wave of communication. I searched for messages about Palin crossing the border [Boynton, March 16, 2010] and found messages by 367 persons. I checked to see how many followers the 367 had. They had 366,000+ followers each of whom received the message. Later it will be clear that 1 to 1,000 is at the edge of the distribution, but it is clear that opinion leadership is going on and that the evidence for studying it is plentiful.

Four, this is global communication, and we should have that as part of our starting point for understanding the streams of communication [Boynton, 2010]. Of course, some subjects are primarily interesting to citizens of one country and not others, and there are many countries. But this is not just American politics. And there are many subjects that are not limited by country boundaries. Communication about Osama bin Laden or about the conflict in Afghanistan or about terrorism come in many languages. Communications about COP15, the UN meeting of nations planning for the global environment, were in many languages. And Twitter has announced that they are going to turn on automatic translation. You will be able to write in English and be read in Chinese or read in English a communication written in Turkish. Globalization really takes off when language becomes less of a barrier to communication. The globalization of communication and its consequences for changing political organization was one of the central themes of Karl Deutsch's scholarship [1953]. What he followed in the changes in Europe is about to re-surface for the global domain.

The Research

In 2009 Twitter came of age as a domain for political communication. When the Nobel committee announced that President Obama would be awarded the Peace Prize a deluge of messages followed; in the next month there were 90,000+ messages about Mr. Obama and the Peace Prize. COP15 met in Copenhagen in December, and that generated over 200,000 messages about the state of the world and what governments were and were not doing to improve it. Health care reform generated hundreds of thousands of messages in 2009 as the House and Senate considered separate bills. And the first Twitter political movement was born with #Teaparty. In 2010 the controversy between Google and China has generated 300,000 messages, and the earthquakes and the tragedies they produced in Chile were commented on more than 200,000 times. And health care returned in Congress and in microblogging with 99,000 messages in a single day.

Microblogging is big and it is new, and political scientists have not given it much attention. Anstead and O'Loughlin have a nice paper tracing twitter reactions to the discussion on a very controversial BBC Question Time [Anstead and O'loughlin, 2010]. Williams and Gulati [2010] compare the use of Twitter and other social networking systems by members of Congress. Lassen, Brown and Riding [2010] look specifically at adoption of Twitter use by members of congress. David Sparks uses connections in the twitter-verse to locate ideological connections [2010]. And I have written a dozen brief analyses about political messaging on Twitter [Boynton]. I am sure there is other work that I have not encountered, but it should be noted that everything I know about is dated 2010. We have not been at this very long.

Context is not available when starting research in a new domain. How big is big? Well, Anstead and O'Loughlin captured 91,000 tweets in 24 hours. Is that big or little? Relative to what? I captured 99,000 messages using the hashtag #hcr one day in March as health care reform came to a head. That is the most I have found for a single day. Most of the streams I have captured that developed into large numbers of messages started with 20 or 30 thousand messages the first day. What are numbers of messages by members on Congress relative to these? Senator Claire McCaskill is the most active user of Twitter in Congress, and she has sent 1465 tweets. That is small relative to many politically relevant streams. Is it big or small relative to not-members of Congress tweeting about politics? And the questions could go on.

The objective of this paper is to use the 125 streams of Twitter messages I have captured to provide some initial context for our research on microblogging and politics.

Data collection

The streams vary greatly in size. They vary greatly in subject matter. I do not believe a sample of political messages or political streams is feasible. Sophisticated reading of messages, which is required to determine 'political,' over the course of a year for a stream that is 50 million messages a day is not feasible. So these are streams I selected because they seemed worth following. There is an over-emphasis on streams that The Washington Pose declared 'breaking news.' I am interested in what is important inside and outside the beltway. So I have some streams for this research that I might not otherwise have collected. I am glad Anstead and O'Loughlin captured messages about the BBC Question Time. I would not have thought to follow that stream, but I have learned from their work. That is how we are going to come to understand the phenomenon -- by learning from each other's research.

The procedure for collecting the messages is pretty straightforward. I use a computer program Archivist that will search the Twitter api for any term given to it. It conducts the search every five minutes because there is a limit on the number of messages Twitter will permit being captured at a single search. I have not found any streams 'flowing' faster than 1500 messages in five minutes.

Choosing a search term is often obvious but sometimes initial research is required. To capture messages about the earthquakes in Chile 'earthquake chile' is likely to get most of those messages. However, there will be messages that the search term does not capture, and it is impossible to know what they are. When the appropriate search term is not obvious then you can search with different search terms to see which come closer to capturing what you want. And there are times when you have to capture a 'contaminated' stream because there is no way to use search to choose appropriate messages and reject others. 'Rino' is both a music group and a term used by Teaparty tweeters to characterize Republicans who are not sufficiently 'with the program.' There is no easy way to distinguish messages about one from the other. So I will capture and then clean up. Language is very flexible. The same can be said in many different ways. That means searches will be imperfect collections of what is being written about the relevant politics.

Once the search term is set the collection is a pretty straightforward process. In practice I have had some difficulties keeping up the searches when I travel -- as at the 2010 International Studies Association meeting in February. But I believe I have missed very few tweets relative to the total quantity I have captured.

I started collecting streams of messages toward the end of July, 2009. The number of searches started in each month is:

Table 1. Month Stream Collection Began |

||||||||

July |

August |

September |

October |

November |

December |

January |

February |

March |

4 |

8 |

14 |

22 |

42 |

9 |

7 |

12 |

7 |

October and November were the big months for starting collections. Earlier I was figuring out how to do the searching. And later I was collecting a number of streams connected with health care reform, and it was difficult to add new collections because of the number that were ongoing.

How long does a stream last? That is, of course, dependent on the researcher as well as the messaging activity. In general I have tried to let the streams go down to very few messages a day, but there are streams for which that will not happen. 'Terrorism' is a stream of messages that is very unlikely to go away for the foreseeable future. And one might only want to know about a specific period -- the day of the State of the Union address, for example. With the caveat that there are about ten ongoing streams in this set the streams lasted an average of 63 days with a standard deviation of 63. The number of days streams lasted divided into quintiles is given in Table 2.

Table 2. Number of streams lasting number of days in quintiles |

||||

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

1-12 days |

13-23 days |

24-43 days |

44-135 days |

136-244 days |

The 25 streams ending most quickly lasted between 1 and 12 days. For this research most of the longest running streams were connected with the politics of health care reform. Some continued long after they might have been stopped, but I could not be sure that they would not re-surface with changes in the politics. So, they got stretched. The general pattern is steams over a period of time. A few have 'gone away' in a brief period, but most that I chose to follow had staying power.

Distributions

In the fall of 2009 three celebrities who are usually identified by a single name did a big deal. I was too late to capture messaging about Tiger's fall from grace. But I did capture the messages about Oprah's announcement that she would not continue her TV show past its contractual limit of 25 years. And I did capture the messages about Obama being awarded the Nobel Prize of Peace [Boynton, November 29, 2009]. Oprah is a big deal. The Nobel Prize is a big deal. Do the streams of messages bear out our view that these are 'big deals'? Oprah's announcement in November produced messages to the tune of 1.2% of the almost 50 million messages that day. The announcement of the Nobel committee about Obama generated 4% of the messages that day. The total messages over roughly the next month was 90,000+ for Obama and 74,000+ for Oprah. The point is we have a better conception of what we mean by 'a big deal' on Twitter if we can make comparisons.

So, the rest of the paper is about distributions that will permit comparisons. I will provide the appropriate summary numbers for the distributions. And I will also display the distributions in quintiles, which is particularly easy to do since I have 125 streams. Quintiles makes a direct comparison with other research straightforward.

Three distributions are important: the total number of messages in a stream, the dynamics or how the messaging changes over time, the use of connection conventions, which includes the reach of the messaging or number of followers.

Total number of messages in a stream

The range in the messages per stream is very great. The stream with the smallest number of messages was 'hack baidu,' which was a stream of 35 messages about the controversy between Google and China. A very few people thought it would be funny to have hacking turned back on Baidu, which is the leading Chinese search engine. As is obvious, it did not take off. The stream with the largest number of messages was #hcr with a total of 586,382 messages, and still counting.

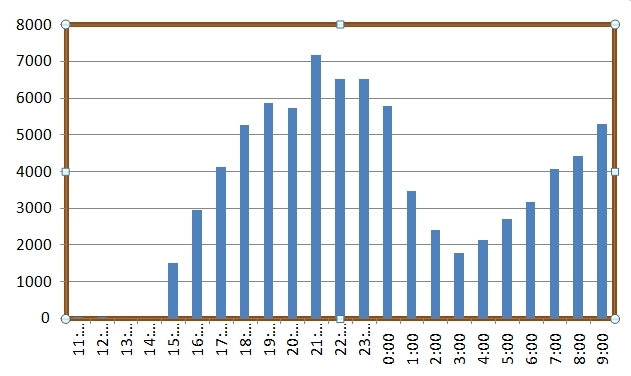

The top two streams, #hcr and 'Google China', are so large relative to the other streams that they dominate any attempt to picture the distribution. I left the top two out in making figure 3.

Figure 3. Total number of messages per stream |

|

The figure shows that the distribution is long on small streams and has only a few very large streams. The mean and standard deviation reflect the same thing. The mean messages per stream is 31,218, and the standard deviation is 70,246. The mean and standard deviation include all of the streams.

Dividing the streams into quintiles makes the same story, but gives more detail about the distribution.

Table 3. Total messages per stream by quintile |

||||

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

35-1295 |

1375-3132 |

3270-8596 |

9063-33870 |

44764-586382 |

Almost four-fifths are below the mean, and the top fifth goes to gigantic streams. At least they are gigantic streams for this data collection.

Dynamics

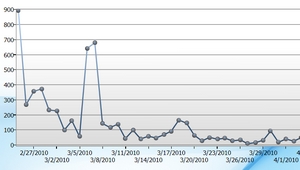

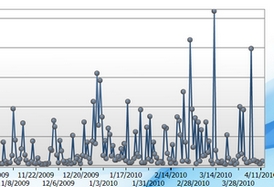

Dynamics is a message stream in time. The easiest way to grasp differences is with figures that have time on the x axis and the number of messages per unit, in this case day, on the y axis. Figure 4 shows three patterns that 'capture' almost all of the dynamics of the 125 streams.

Figure 4. Dynamics of messaging over time |

||

Spike and decay |

Several spikes |

Volatility |

|

|

|

Spike and decay is a figure based on messages naming Congressman Stupak at the time he was negotiating on the health care reform legislation and afterwards for a couple of weeks. The first day is the largest number of messages and messaging declines each day after in a relatively smooth fashion. The figure illustrating several spikes is a series of messages about Marjah in Afghanistan. The first day was when the US-Afghan military took over the area. Then the spikes after that occur as people communicated about events there. The figure on the right, volatility, is based on the stream of messages about suicide attacks. Messaging is responsive to the incidence of suicide bombing attacks. The report of an attack generates a stream of messages, but the stream goes away about as quickly as it goes up. Attention is very short lived. And there are lots of reports of suicide attacks so the figure is full of increases and decreases in messaging.

Almost all of the streams can be characterized in one of these three ways.

Table 4. Three dynamics of message streams |

||

Spike and decay |

Several spikes |

Volatile |

65 |

30 |

26 |

An earthquake happens, Google announces that they are not going to continue censoring their searches, a person who is the pivotal point in a vote asserts a demand. The events attract attention of those who had not been attending to Chile or Google's relationships with China, or the demand of the members of congress allied with Mr. Stupak and messaging climbs very quickly. This is the most common pattern with 65 of the 125 streams fitting this pattern. Several spikes and many spikes, or volatility, are about equal in number in these 125 streams.

Connections that make a stream

Twitter provided one mechanism for making connections. You could follow a person whose tweets you wanted to read. When you follow you automatically receive all of their tweets. That, of course, became a race for the top. But below Ashton Kutcher and the others in the race people used this capability to keep up with news, to keep up with friends, and in politics to keep up with and express their views about what was happening. However, following is not very much connection so three other conventions developed that helped extend connectivity. They are the hashtag, the retweet, and including a url. They make connections in somewhat different ways. The hashtag identifies the audience with whom you want to communicate. It also helps identify the subject of the message. Retweeting is quoting someone else's tweet and 'sending it along.' And the url connects the message to a world beyond Twitter, and usually a text that is considerably more than 140 characters.

Following

The relationship of following is an important foundation for opinion leadership. One's messaging is addressed to others. If a person has 1,000 followers that is 1,000 people who are going to receive messages about the subjects the person finds interesting and important. It is calling attention to this and not that. It is also about the construction of the presentation. Teapartiers, for example, put a very different construction on health care reform news than did others. In the stream of messages about Reid's health care bill how many people are receiving the messages of the stream? How extensive is the leader-follower relationship and thus how much spread is there of 'the word' of the leaders? It is possible to check the number of followers of everyone in a stream with their Twitter account. That would be, of course, a very big task. Short of that task I decided to check the followers of the 10 people with the most tweets in each stream. The total number of followers for the 10 most active tweeters for each stream is well over 3 million. The average number per stream is 25,000+. However, this is again a very skewed distribution, and the division into quintiles is a more useful description of the distribution.

Table 5. Number followers for top 10 tweeters by quintile |

||||

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

1,269-10,882 |

10,911-15,939 |

16,020-20,005 |

20,571-32,333 |

32,610-652,559 |

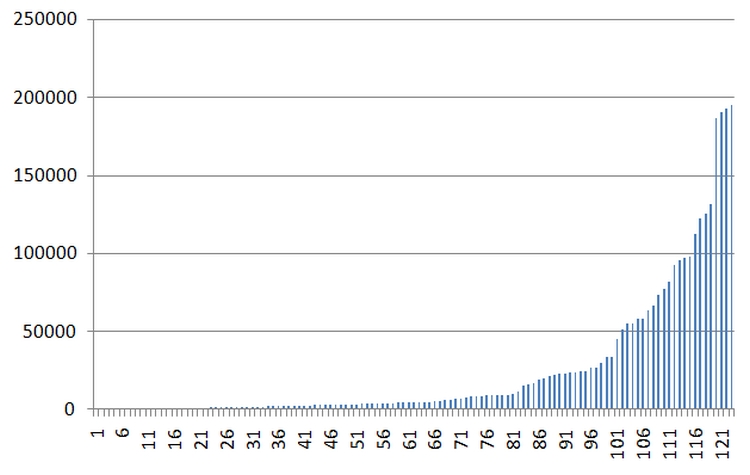

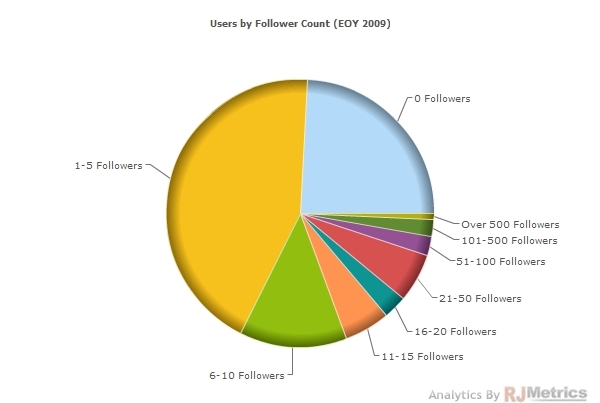

For most streams the number of followers in the bottom four quintiles are below the mean. Only some in the fourth quintile and all in the top quintile do they range from the mean up. There were 93,000 messages remembering 9/11 over a seven day period. The number of followers of the ten most active was 122,373. That is 12,000 apiece. When ten individuals can reach 122,000+ plus followers you have very great spread of their messages. The top is very impressive, but equally impressive is that in the top four quintiles the most active could reach no fewer than 1,000 followers apiece. When I said that the 1 to 1,000 ratio for 'Palin crossing into Canada' was at the edge I meant it was at the low end. The number following the 10 most active about Reid's health care bill was 31,280 or three thousand each. Four-fifths of these individuals can reach more than a thousand persons with their messages. How exceptional this is can be seen in this figure from a report by RJMetrics [RJMetrics, January 26, 2010].

Figure 5. Followers per Twitter account, late 2009 |

|

The number of twitter users with 500 or more followers is a tiny sliver of the pie chart. Most of the top ten most active on these streams fall into that tiny sliver. People choose to follow them. People choose to follow them in very big numbers. Opinion leaders seems a most apt characterization.

Conventions

Three conventions emerged that have a substantial impact on the ability to connect streams of messages. The use of these conventions in messaging about politics is quite unusual, and that helps us better understand how these streams of messages are operating, what they are, and how they are different from most Twitter messages.

In the first half of 2009 researchers at Microsoft took a sample of 720,000 twitter messages [Boyd, Golder, and Lotan, 2010]. The results for the three conventions were:

The growth curve of messaging means that the number of tweets in the first half of 2010 dwarfs the number of tweets in the first half of 2009. We do not have any way to know how much the distributions the Microsoft researchers found remain accurate today. But it is all we have. So these findings serve as a frame for interpreting the results for the 125 streams about politics.

Urls function as important extenders of the message. They are almost always used either to say 'did you see that' where the that is in the document specified with the url or they are used as evidence for justifying a claim where the evidence is in the document specified with the url. In both cases they point the reader beyond this message. They connect the message to the political world outside of Twitter.

For these streams the percentage of messages containing a url [http://] ranges from 29% to 98%. The mean for all 125 streams is 69% and the standard deviation is 16.7%. When divided into quintiles:

Table 6. Percentage messages per stream http:// by quintile |

||||

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

29% - 51% |

51% - 67% |

67% - 75% |

75% - 84% |

84% - 98% |

This is very different from the Boyd, et al finding. The political streams are out on the fringe of the distribution for all Twitter messages. Political streams of messages are about politics. Much of the rest of Twitter is about the self. The standard claim about Twitter is that most messages are as trivial as what one had for breakfast or what town you are driving through. They are not trivial to the individual and, perhaps, a close circle of friends. But they are not about public affairs in the same way the political streams are. The large difference need not be surprising, of course. The messages were chosen because they were about public affairs. That they use the url to point to public documents seems that it might be expected. It does, however, mark off these messages from the 'mainstream' of Twitter messaging.

Retweeting is quoting another twitter message. It is usually done by starting the message with "RT @[name of original author] original message." At times the @[name] is left off, which is why the Microsoft researchers have a rather elaborate description about how they searched. What is the point? It is a continuation of the 'pass it along' syndrome. The person saw it, liked it, and wanted to pass it along to followers and anyone else who might come across it. It is about circulating ideas through the network, and technology blogs have thought it important as the mechanism of going viral, which they think of as important.

The Microsoft reseachers found that 3% of their sample included retweets. The range for the streams about politics is from 4% to 72%. The mean is 37.5% and the standard deviation is 13%. When divided into quintiles --

Table 6. Percentage retweets per stream by quintile |

||||

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

4% - 27% |

27% - 34% |

34% - 40% |

40% - 47% |

47% - 72% |

While retweeting is not as prevalent in these streams as is using url the incidence of retweeting is much higher than found in the sample drawn by the Microsoft searchers. This emphasizes the point about using urls. Twitter is used in political messaging as a public domain in which individuals are sharing what they know and what they think about public affairs. These streams are public affairs. Twitter becomes an enlargement of the public domain. Just as the media corporations must move over in the face of new streams of news so the argument in the public domain is expanded by microblogging. All of the institutions that have been designed to circulate ideas -- interest groups, for example - will have to move over for this expansion of their domain [Karpf, 2009].

Hashtags are an invention specifically for communication with Twitter. The format is #[a string of characters]. The string of characters might be a word, such as #Obama, but also might be either a wholly invented designation, as with #hcr, or it might be a string of words run together, as in #iamthemob which I think is a very interesting self designation. Boyd et al found that 5% of their sample contained a hashtag. The numbers for the streams I have collected are not easily averaged. Twenty-three of the streams were found by searching for a hashtag. #hcr, for example, is a stream of messages. There are 585,000+ messages and everyone of them contains the hashtag. The same is true of #Palin, #teaparty, #welovethenhs, #cop15, and others. If you look at only the streams that are not identified by containing a hashtag the range is from 1% of the messages that were a response to the death of Senator Ted Kennedy to 79% for messages about an Iranian protest in November 2009. The Iranian protest in February 2010 was next highest with 78% containing a hashtag. The mean for the 102 not identified by a hashtag is 19.7% and the standard deviation is 12.5%. Including all 125 streams and dividing into quintiles gives

Table 7. Percentage per stream containing hashtag by quintile |

||||

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

1% - 13% |

13% - 16% |

%17 - 23% |

23% - 58% |

77% - 100% |

I believe we should understand the hashtag as generally identifying an audience with whom the tweeter wants to communicate. When someone adds #cop15 to their message that seems unlikely to be an after thought. It is a way of entering into a stream of communication that is well known and well practiced. #cop15 is a specific meeting of nations to make plans for saving the global environment. But hashtags are also used as name of groups as in #teaparty or #p2, which is a designation for progressives. When they are added to a message it does not so much indicate what the message is about as who might be interested in this message. So local meetings of teaparty organizations can be advertised to people who are interested by using the #teaparty hashtag. Hashtags is not the only way to constitute a stream of messages, but for those I have collected they seem to be an important element in constituting the stream.

Conclusion

It is 50 million messages a day. It is a global phenomenon with message from almost all countries. There is no end to the subjects that people are adding to this giant river of communications. Politics may not be the favorite subject among the messages, but a small fraction of 50 million a day is a big number. Communication requires readers as well as writers, and they have to find each other. The conventions are designed to help make the connections.

As political scientists what we have to see in this messaging is an augmented public domain. The public domain has been monopolized by the few -- the media and whoever they were willing to attend to -- because of technology. There are still countries, China and Iran are two good illustrations, that want to close down any opening of a public domain to citizens. But what has been opened is very unlikely to be closed. 'Leaders' are going to have to move over as the not-leaders enter the public domain in ways that were not possible in the past. This public domain is even messier than the domain dominated by TV in the US, which is taking on a very different form than the practices of the past. If you like neat you are not going to like this new world very much.

References

Nick Anstead and Ben O'loughlin (2010) The emerging viewertariat: explaining Twitter responses to Nick Griffin's appearance on BBC Question Time.

Danah Boyd, Scott Golder, Gilad Lotan, "Tweet, Tweet, Retweet: Conversational Aspects of Retweeting on Twitter," hicss, pp.1-10, 2010 43rd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, 2010

Boynton list of brief analyses http://www.boyntons.us/website/new-media/new-media.html

Boynton (November 29, 2090) How big is big? and why would one be interested? http://www.boyntons.us/website/new-media/analyses/how-big-is-big/how-big-is-big.html

Boynton (February 1, 2010) Twenty-four Hours Tweeting the State of the Union, http://www.boyntons.us/website/new-media/analyses/state-union/twenty-four-hours-tweeting.html

Boynton (February 17, 2010) Global Communication Reconfiguring Power, paper presented at the 2010 International Studies Association annual meeting. http://www.boyntons.us/website/new-media/analyses/isa2010-globalcommunication/global-communication.html

Boynton (March 16, 2010) Sarah Palin did what? The Importance of Redundancy, http://www.boyntons.us/website/new-media/analyses/redundancy-palin/redundancy-palin.html

Karl W. Deutsch (1953) Nationalism and Social Communication, Cambridge, New York MIT Press-Wiley

GigaTweet, http://popacular.com/gigatweet/

Robert Huckfeldt and John Sprague (1987) Networks in context: the social flow of political information, The American Political Science Review

David Karpf (2009) The Moveon effect: disruptive innovation within the interest group ecology of American politics, presented at the 2009 American Political Science annual meeting

Elihu Katz and Paul Felix Lazarsfeld (1955) Personal Influence: the Part Played by People in the Flow of Mass Communications

Marshall Kirkpatrick (February 22, 2010) Twitter Hits 50 Million Tweets Per Day, ReadWriteWeb

David S. Lassen, Adam R. Brown, Scott Riding (2010) Twitter: The Electoral Connection? presented at the annual meeting of the Midwest Political Science Association

Paul Felix Lazarsfeld, Bernard Berelson, Hazel Gaudet (1944) The people's choice: how the voter makes up his mind in a presidential campaign, Columbia University Press

Pew Foundation, News Interest Index, http://people-press.org/

RJMetrics (January 26, 2010) New data on Twitter's users and engagement, http://themetricsystem.rjmetrics.com/2010/01/26/new-data-on-twitters-users-and-engagement/

David Sparks (2010), Net Style: Members of Congress in the Social Web, presented at 2010 Midwest Political Science Association.

Christine B. Williams and Girish Jefferson Gulati (2010), Communicating with Constituents in 140 Characters or Less: Twitter and the Diffusion of Technology Innovation in the United States Congress, presented at 2010 Midwest Political Science Association.